Juju Watkins suffered an ACL tear in USC’s Round of 32 game Monday night — shedding a light on the growing number of ACL injuries in women’s sports.

Juju Watkins transcends sports – men’s or women’s. The presumed National Player of the Year was on her way to a National Championship run when she went down in the first quarter of USC’s game against Mississippi State Monday Night. Hours later, it was announced she suffered an ACL tear in her right leg and will undergo surgery.

It is a devastating thing to come to terms with for the women’s basketball community. Watkins averaged 23.9 points per game in her sophomore season at Southern California. She helped her team beat UConn once and UCLA twice, winning a Big-10 regular season championship and making it to the Big-10 championship game. The Trojans were on track to make a deep run in March Madness with Juju at the helm.

She’s a giant in the sport even as a sophomore — she is signed on NIL deals with Nike, Gatorade, State Farm and more, and even invested in Unrivaled basketball. She is on track to be drafted into the WNBA in 2027 — with many hoping the Toronto Tempo are able to secure the no.1 pick needed to pick her up.

This injury will sit her out for about a year, depending on if she decides to redshirt her entire junior season or not. If she does redshirt, she will retain a year of eligibility in the NCAA but also won’t be able to come back to the court until the start of the 2026-2027 NCAA season.

Watkins joins a long list of women’s basketball players who have suffered a tear to their Anterior Cruciate Ligament in recent years. Cameron Brink, Kia Nurse, Sue Bird, Olivia Miles, Paige Bueckers, Azzi Fudd and more are among the club no one wants to be a part of.

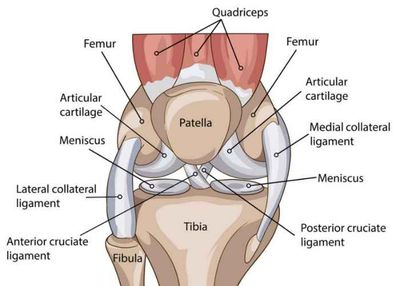

The ACL is a small ligament that connects the lower leg to the thigh in the knee. There are two ligaments that criss-cross each other right in the middle of the knee — the ACL and the posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) — that create motion in your knee. They are essential in movement and stability of the leg.

The ACL in particular prevents the tibia bone (lower leg) from sliding in front of the femur bone (thigh) and provides rotational stability. The PCL is much stronger than the ACL, which means it is injured less.

ACL injuries are common in sports because they happen when a person changes direction rapidly, stops suddenly, slows down when running, lands from a jump wrong, or collides the knee. Luckily the prognosis is usually good with surgery and recovery time, and professional athletes (especially the younger they are at the time of injury), have a high rate of returning to sport after these injuries.

In recent years, there has been a large surge of women’s athletes who have suffered ACL tears. According to the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, women are more likely to suffer this injury due to differences in physical conditioning, muscular strength, and neuromuscular control, according to studies. Other studies have shown that the female pelvic and lower extremity alignment can cause higher rates in ACL injuries in women. There is also evidence to connect the increased looseness of ligaments due to hormonal differences in the female body can make ACL tears more frequent in women.

Yet, despite these findings, there has been little research on how these injuries can be avoided for women specifically. Only 35% of all sports science research is done on women, per the Polytechnique de Paris. That means that the training programs, diets, and recovery that professional women’s athletes do were designed for men, with their physiological make up in mind.

In a study published in the Journal of Knee Surgery, it was determined that most ACL injuries in the WNBA happen to guards and forwards. This is because of their increased need to run, jump, and drive to the basket. These injuries also happen more often in games than practice due to the intensity of the game environment.

So there is evidence that these injuries are more likely to happen to women, but what are we doing about it? There have only recently been studies done to see how aligning training with a player’s menstrual cycle can have affect on their long term health and sustainability in sports. There is also a call to study the effects endometriosis has on training in women’s sports. There ultimately needs to be more research done to figure out how women’s sports training team and athletic staff can create training programs that align more with female physiology and endocrinology.

With women’s basketball growing, the ever growing list of players missing time with ACL injuries is only going to have negative impacts on the sport and its growth. More than that, the long-term health of these athletes needs to be at the top of the priorities list. Creating training programs that aren’t designed for the make-up of their bodies will only lead to more injuries and shorter careers.